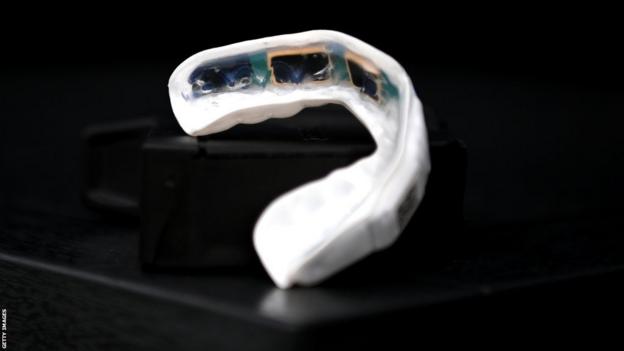

Smart gumshields that record the forces involved in collision sports are being used in the men’s Six Nations for the first time.

The gumshields, which contain a chip to record gravitational forces, are being gradually rolled out in professional rugby union.

Few doubt that represents a step towards helping to better understand collision sports, but some of the research has been questioned by concussion experts, and there are calls for further change.

Here’s what you need to know.

What is the background?

Rugby union faces a crisis over safety, with hundreds of former players taking the game’s governing bodies to court over the management of head injuries during their careers.

In October, World Rugby confirmed smart mouthguards would be worn at the WXV – a new international competition – before being brought in worldwide from January 2024.

That came after several trials and two academic studies funded by World Rugby – the results of which it said provided “players and parents with greater confidence than ever before into the benefits and safety of rugby”.

In October, chief medical officer Dr Eanna Falvey told BBC Sport the introduction of gumshields would be a “really positive” change.

The gumshields – made by Prevent Biometrics – record the gravitational force (G-force) and direction of force involved in contacts, which are known as “head acceleration events”.

They can provide real-time data to a doctor or official on the sidelines, and be utilised to inform the Head Injury Assessment (HIA) process players go through after head contact.

What did World Rugby’s research say?

World Rugby funded the Otago Community Head Impact Detection study (Orchid) and its Elite Extension study, which was undertaken by Ulster University.

The Orchid study used smart gumshields to examine cumulative head acceleration events (HAEs) in male rugby players in New Zealand from the under-13 age group through to elite level.

It found 86% of forces on the head in community rugby are the same or less than those experienced in general exercise such as running, jumping and skipping, while 94% are lower than those previously measured on people riding a rollercoaster.

The Elite Extension study, which looked at both men’s and women’s rugby, found most contact events in the elite game do not result in significant force to the head, though forwards are more likely to experience force events than backs.

World Rugby said the data provided “a complete picture of playing rugby like never before”. Its chairman Sir Bill Beaumont – a former England captain – adding the Orchid study was “concrete proof” the organisation was putting time, energy and effort into making the sport even safer and would “never stand still on player welfare”.

World Rugby has developed minimum specifications for smart gumshields – which include independent testing – and says it will review them every six months.

The Prevent Biometrics gumshield was chosen for roll-out as World Rugby said it was the only manufacturer to meet its specifications.

A trial in 2019, when players from Welsh clubs Ospreys and Blues wore smart gumshields during a Pro14 match, used Protecht gumshields.

What has been the criticism?

The Orchid study’s lead author acknowledges the technology is still in its infancy.

Professor Melanie Bussey, of the University of Otago, said: “Player safety is our utmost concern, and this technology is giving us the best chance we have of understanding the multifactorial nature of head injury in sport.

“But we need a lot more research to understand the clinical relevance of this data. That is how science works.”

However, two concussion experts have said data from force events below 10G should have been disregarded, and there should have been greater detail for data recorded over 60G.

Events under 10G are similar to those experienced riding a rollercoaster or trampolining. Recent studies have found American Football players diagnosed with concussion had HAEs ranging from 40-150G.

Professor Alan Pearce, of La Trobe University in Melbourne, said it was “quite puzzling” that all forces over 60G were grouped together in the study.

“There is plenty of evidence to say that there are a lot of impacts, not just concussive impacts, above 60G, so it takes out a lot of data,” he added.

“Rugby is saying a lot of the hits are no different to skipping and running… that’s a clear case of if you’re starting to collect data below 10G, well you can say things like that.”

The main author of the Elite Extension study said all impacts above 60G were grouped together because there were such a low number of them.

But Dr Doug King, a New Zealand-based expert in head injury and head biomechanics, said concussions often occur above 90G and was therefore concerned the data was not showing “the full picture”.

An academic paper presented to the International Research Council on Biomechanics of Injury last year said the technology in the Prevent gumshield underestimated acceleration in higher-speed impacts

Professor Damian Bailey – director of the Neurovascular Research Laboratory at the University of South Wales – said: “There are justifiable concerns that some of the really big impacts that can really cause damage are going to be missed – going above 100G, for example.

“It can be quite rare, but these are events that are really important to capture.”

In a statement, Prevent Biometrics said its Intelligent Mouthguard system was “the most widely evaluated and independently scrutinised head impact sensor on the planet” having gone through “thousands” of laboratory tests that were peer-reviewed and published.

World Rugby said the studies were independent, and data had been “accurately reported in full and independently peer-reviewed”.

Of the seven co-authors of the Orchid study, five declared conflicts of interest, and two co-authors of the Elite Extension study were declared as World Rugby employees.

While it is common for sporting bodies to fund academic research, Prof Pearce said “a number” of scientists were “very concerned about the independence aspect”.

“We’re walking a very fine line between true independent research where funding organisations, including sport, should be able to give the money but have absolutely no involvement whatsoever,” he said.

In response, the lead author of the study told the BBC that World Rugby was “not involved in the study’s data processing, data analysis and interpretation of the research or outcomes” of the research to protect its integrity.

Prof Bussey added: “As academic researchers we have our own ethics and standards to uphold. Our research stands as independent work that has been published in one of the top scientific journals in our field and has been independently peer-reviewed by multiple, highly reputable, senior researchers in our field.

“We stand by our findings and our own integrity as researchers. From the outset our position with world rugby was that ‘we will follow the data wherever that takes us’.”

What else can be done?

Former Wales player Alix Popham was diagnosed with early onset dementia in 2019, and is one of almost 300 former players suing rugby union’s governing bodies for negligence, claiming that playing the sport caused his brain damage.

He has called for more changes to be made “as soon as possible” to protect players.

“The knowledge has been there for decades in rugby,” said the 44-year-old, highlighting that in 1977 a three-week stand-down for concussed players was introduced.

“People need to know the truth how often these car crashes are happening.

“In the NFL, they’re allowed to do 14 padded sessions per year. A rugby player could do that in 6-8 weeks. That, overnight, could make a huge difference to a player.

“Rest in between seasons as well… there are some players from South Africa and Argentina who are playing 12 months a year.

“You need to address the problem, draw a line in the sand and make the changes.”

Dr King wants greater emphasis to be put on injury management and the number of impacts a player experiences, rather than the size of them.

“If you get a concussion, you should be out for three months,” he said.

“I think the ultimate goal of all this is managing the injury. If you have a fractured leg, how long are you off? Because you can’t run on it or do anything with it. Everyone knows because they can see a big plaster on it.”